Hitler in Paris (2)

Hitler in Paris (2)

If they look, smell and waddle like generals, they must be generals – unless they are architects and sculptors and who knows what else.

Depicting power

A picture editor looking for a cover photo for a book on Hitler and his top military officials is spoiled for choice.

A picture editor looking for a cover photo for a book on Hitler and his top military officials is spoiled for choice.

The cover of the 1989 edition of Correlli Barnett’s discussion of 26 of Hitler’s generals uses nine thumbnail head shots against a muted background of a military parade.

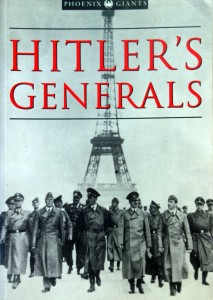

The book was reissued a few years later with a dramatically new look, featuring the Führer and presumably – given the book’s prominent title – his generals (and their adjutants and other aides).

The book was reissued a few years later with a dramatically new look, featuring the Führer and presumably – given the book’s prominent title – his generals (and their adjutants and other aides).

The Eiffel Tower is prominent, not muted, in the background. This picture was shot on location, and the original shows an uncropped and imposing Eiffel Tower.

A similarly titled 2002 book – Hitler and His Generals, edited by Helmut Heiber and David M. Glantz – uses the familiar image of the Führer poring over a military map surrounded by top military aides.

Of the three pictures, the Paris-Eiffel Tower shot is clearly the most powerful, conveying the German military machine at a moment of immense success.

Hitler’s architectural adviser Albert Speer is to his immediate right, and sculptor Arno Breker to his left.

In fact, the German leader envisioned and organized this Paris visit – the only time he ever visited the French capital – as an artistic, not militaristic, occasion.

He gave pride of place not to his Field Marshals or generals but to his main architect, Albert Speer, on his right, and to sculptor Arno Breker on his left. Also in the group is another architect, Hermann Giessler.

In his Inside the Third Reich, Speer notes that Hitler personally invited him to join this “art tour”. (These are Speer’s quotation marks. Is he quoting Hitler? Or the tour organizer? Or does Speer uses quote marks to highlight the blended personalities in this group and the purpose of the visit?)

Historian Ian Kershaw nevertheless also notes that the purpose of the trip was “cultural, not military.”

Paris Photo Op

The Nazis, loath to miss a propaganda opportunity, fused the artistic with the militaristic.

Speer explains how they came by their overcoats. After they arrived at Le Bourget airport, “Field-gray uniforms had been provided for us artists, so that we might fit into the military framework.” These greatcoats are not ordinary coats. This is the ultimate in power dressing.

The civilians, then, are dressed identically to the generals, and all are overdressed for sightseeing in Paris in late June. Propaganda shots were part of the itinerary. Photographers – still and newsreel – accompanied Hitler throughout his brief but high-profile Paris excursion.

These two dozen or so top Nazis and Wehrmacht officials are organized more or less into rows and columns but they are not on parade, not in strict military formation. They are strolling, not marching.

Soldiers walking through a just-occupied city are wary of snipers and other dangers. This group seems not to have a care in the world.

I suspect that numerous photographs were taken of this scene, and the Germans selected this particular image because its blend of casualness and bellicosity exudes enormous, and seemingly natural, arrogance and confidence.

I suspect, too, that the photo editor who selected this shot for the 2002 Barnett book was unaware of its “artistic” nature. It was chosen because the German military had just won a series of stunning victories and seemed unstoppable. Today Paris, tomorrow London and who knows where else after that. Despite the artists in its ranks, these men symbolize that achievement.